0%

Today, the Supreme Court released its decision in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC. Though the procedural circumstances of this particular case limit the scope of this decision’s precedent, it clarifies a long-recognized struggle of lower courts in handling commercialized speech and signals a tough, uphill battle ahead for parody brands. While parody is often covered by the First Amendment, here the Court found that constitutional free speech protections are not triggered when the speech takes the form of a commercial indication of source; under such circumstances, infringed trademarks are still afforded full trademark protection. Parody brands should adjust their practices accordingly in light of this result.

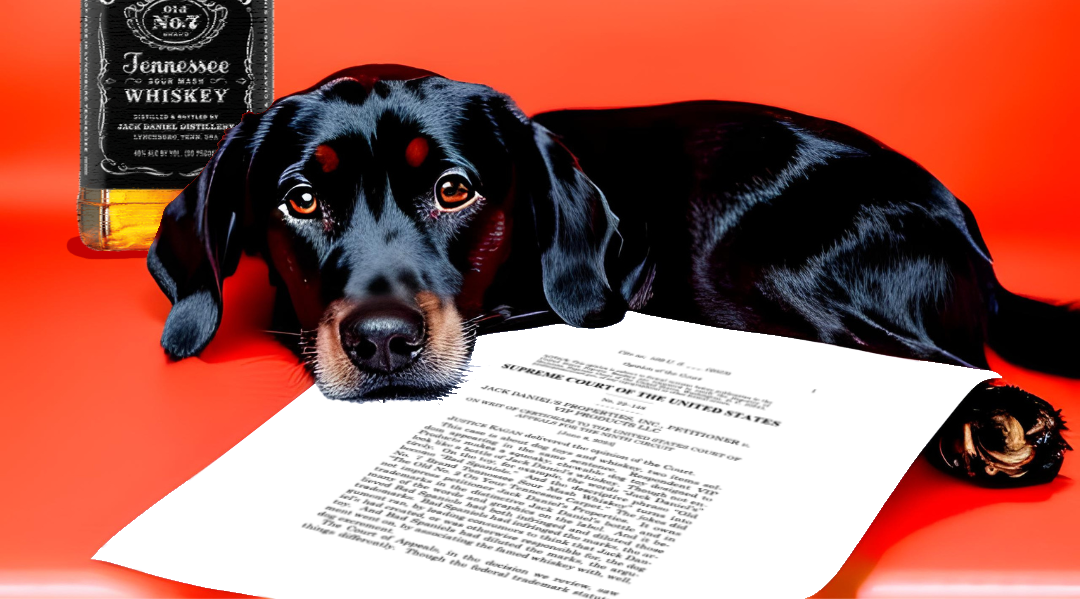

VIP Products designed and sold a dog chew toy in the shape of a Jack Daniel’s bottle, including the alcohol manufacturer’s classic emblematic labeling. Instead of emulating the text of a Jack Daniel’s bottle, however, VIP Products poked fun at the design with dog-themed attributes—replacing “Jack Daniel’s” with “Bad Spaniels,” substituting “Old No. 7 Tennessee Sour Mash Whiskey” with “The Old No. 2 On Your Tennessee Carpet,” and swapping “40% alc. by vol. (80 proof )” with “43% poo by vol.” and “100% smelly.”

Comparison between Jack Daniel’s bottle (left) and VIP Products’ chew toy (right).

This was hardly their first ‘spoof’ dog toy; VIP Products had an entire “Silly Squeakers toy line dedicated to such parodies. “Most of the toys in the line are designed to look like—and to parody—popular beverage brands. There are, to take a sampling, Dos Perros (cf. Dos Equis), Smella Arpaw (cf. Stella Artois), and Doggie Walker (cf. Johnnie Walker).”

Jack Daniel’s disapproved of the use of their mark and trade dress as stylized in the Bad Spaniels parody, sending VIP Products a letter demanding that VIP stop selling toys with such designs and beginning the course of events that would eventually land this case at the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court’s tasks in this case: to determine if, in a trademark infringement action such as this, a court should first conduct a First Amendment Rogers inquiry; and to decide whether this use could constitute a “noncommercial use” under a dilution by tarnishment analysis.

To resolve the latter, the Court walked back the Ninth Circuit’s assessment that any conveyance of a humorous message is to be necessarily regarded as a “noncommercial use,” instead determining that Bad Spaniels would not be granted protection under the noncommercial use exception on this basis.

To answer the former, the Court looked deeper into the interplay between trademarks, parody, and the First Amendment.

The First Amendment has clear protections for wholly non-commercial speech, but such speech was not at issue here. Instead, the Court had to examine how VIP’s use of Bad Spaniels as a trademark would limit implication of the First Amendment in a trademark infringement context.

In its discussion on this matter, the Supreme Court notes that another trademark case—involving yet another defendant who sold a dog product—bore “a striking resemblance to this one.” There, in Tommy Hilfiger Licensing, Inc. v. Nature Labs, LLC, the defendant marketed “a line of pet perfumes whose names parody elegant brands sold for human consumption.” Tommy Hilfilger did not appreciate the defendant’s product “Timmy Holedigger,” and sought trademark redress for this use.

The court in Hilfiger did not apply Rogers. There, the court reasoned that “Rogers . . . kicks in when a suit involves solely ‘nontrademark uses of [a] mark—that is, where the trademark is not being used to indicate the source or origin’ of a product, but only to convey a different kind of message.” Because the Timmy Holedigger mark also functioned “at least in part” to indicate the source of the perfume, the defendant’s use failed to implicate Rogers.

Every dog has its day, and VIP Products’ Bad Spaniels received similar treatment to its dog perfume counterpart. Just because VIP portrays a humorous message in their toy designs does not entitle it to Rogers’ protection. Instead, VIP also used the Bad Spaniels message for other purposes, namely, as a trademark (and VIP,perplexingly, admitted as such in its court pleadings). Because the parody trademark still serves a trademark function “at least in part,” a traditional likelihood-of-confusion analysis is appropriate. The Court further rationalized that such a determination would not be damning to a parody trademark use since a likelihood-of-confusion analysis would have to take into account to what extent the use of parody diminishes the risk of confusion among consumers.

But to be effective in its purpose, doesn’t a parody need to closely resemble the use it is parodying? Wouldn’t a parodic use otherwise fail to be successfully humorous or critical? A Jack Daniel’s parody that looks nothing like Jack Daniel’s insignia would hardly be a parody at all. In what circumstances could a parody mark also serve a trademark purpose, be a viable parody, and not cause a likelihood of confusion among consumers? How should parody brands respond to this decision?

VIP did place a disclaimer on its Bad Spaniels chew toy, which informed customers that the “product is not affiliated with Jack Daniel Distillery.” The Court, understandably focused on the narrow issue of Rogers’ applicability, did not mention how this disclaimer would affect the calculus. Could a proper disclaimer alleviate likelihood-of-confusion concerns? Does it depend on the sophistication of the purchasing audience? Could it likewise depend on the size, flair, and placement of the disclaimer? What other steps should a company that sells parodic uses of trademarks take to dispel concerns of confusion?

Perhaps we will receive some guidance regarding these unanswered questions on remand. Regardless, the commercial viability of parody marks takes a hit after this decision. If nothing else, those who parody other brands in their trademarks must tread lightly in response to Jack Daniel’s Properties v. VIP Products.

Lastly, let’s take a step back to assess if Jack Daniel’s Properties is a step in the right direction from a trademark policy standpoint. There’s no doubt that parody brands have some intrinsic value: there’s a reason a dog owner might buy the Bad Spaniels bottle toy over a plain bottle toy. But is the novelty of parody brands derived exclusively from appropriating the goodwill of more popular brands, or do these parody users add something of extra value through their humorous messages? If the latter, is this an interest we believe is worth protecting? Should that interest, if any, be curtailed in correspondence with the parodied brand’s trademark rights, or should the parodied brand not be contemplated in such analysis, given that the overarching objective of trademark law is not for monopolization of marks on the part of the mark holder but rather for consumer protection purposes?

To the extent that Jack Daniel’s Properties limits the viability of brand parodies and gives trademark owners carte blanche to silence those who poke fun of its trademark in a way that trademarks are intended to function, this decision is a step back. To the extent that Jack Daniel’s Properties instills within those who wish to parody brands the creativity necessary to continue to critique not only a brand’s image but also its commercial reach – and to do so within the bounds of this decision (i.e.—avoid causing a likelihood of confusion) – this decision could compel flexible, new, and original parodic uses in the marketplace.

Again, as mentioned above, it is too early to know the precise practical reach of this decision given its procedural and factual limitations. But it is helpful in such circumstances to fear the worst and project the widest scope, and, in so doing, I arrive at the following assertion: While the Court was right to consider that critical speech in a trademark context need not, as a threshold matter, be as expansively protected as critical and parodic speech in other contexts, its decision in Jack Daniel’s Properties ultimately comes down too rigidly on such parodic voices and obtrusively curtails an entire medium through which effective critique and corporate criticism could otherwise be conveyed.

To view a version of this article with full citations in footnote form, click the PDF link here.