0%

Solo artists or bands who apply to federally register trademark rights in their artist or band name often make similar mistakes in their applications. If not dealt with properly, these mistakes can lead to the USPTO refusing to register these artists’ trademarks. This article discusses a few of these mistakes and details how they can be best avoided. In particular, this article references one of Taylor Swift’s trademark registration applications, the Office Action she received for issues with her application, and the steps she took to overcome these common issues. Although applicable to artists as well, refusals that are common to all applications – such as likelihood-of-confusion, mere descriptiveness, and requirement to add a disclaimer – will not be addressed in this article.

In a trademark registration application, an Examining Attorney will need to see that you use your trademark in connection with your goods or services. The USPTO requires that applicants submit a ‘specimen’ that demonstrates such use.

It is not uncommon for artists to have their trademark applications refused because they misunderstand this specimen requirement. For these applicants, many of them simply provide an image of their mark. But the mark itself is to be submitted under the “Drawing” section of the application—re-submitting the mark itself as the specimen fails to demonstrate that the mark is being used in connection with the goods or services. For example, a band that wants to register its name as a trademark in connection with sound recordings must submit a specimen that shows the band name used in a place where sound recordings are available to consumers. A screenshot from Spotify or Apple Music – which clearly shows the website url and displays the date the screenshot was taken – may suffice, but see the next section for more information.

This is the most common reason for an artist specimen to be refused: the specimen must show the trademark used in relation to a series of songs. In this way, a screenshot of a single that an artist released on Apple Music will not serve as an acceptable specimen.

Trademarks as Consumer-Protecting Source Indicators

The rationale behind this requirement makes sense in its context within trademark law. At its core, the central function of trademark law is to protect consumers’ expectations in the marketplace as they pertain to the source of goods or services.

For example, most consumers acknowledge that Nike has a positive reputation for its athletic apparel and footwear. If you were to go into a sporting goods store to purchase cleats, and the store had a pair of cleats with Nike’s wording and logo on it, you would reasonably assume that Nike manufactured the shoe. If you then proceeded to purchase the shoe based on Nike’s reputation regarding shoe quality and performance, you would subsequently be disappointed to discover that the shoe was in fact produced by a lower-quality manufacturer.

This is precisely the harm trademark law seeks to prevent. By providing Nike the exclusive rights to sell specific goods with the NIKE name on them, consumers can trust their expectations regarding the source of goods are in line with reality. All brands that function as a trademark carry expectations about quality and source, from RUTH’S CHRIS to SPIRIT AIRLINES.

How a Series Is Necessary To Indicate Source

But why the requirement for a series for songs? Nike again serves as a fine example, this time regarding how a brand might fail to function as a trademark. If you see an individual wearing a shirt you like with NIKE lettering, you can then seek to purchase the shirt for yourself by going to the identified source. Consider if that shirt were one-of-a-kind: Nike only produced one garment, and that individual you saw purchased it. Under those circumstances, the NIKE lettering does little to indicate source; you cannot make informed purchasing decisions if goods or services are not available for purchase. A company needs to produce a quantity higher than one of a product (or provide services on more than a one-off basis) for any branding on the product to function as a trademark.

Generally, any company that sells a product seeks to sell as many units of that product as possible, so in most industries, the requirement that a specimen demonstrate use in connection with a series is not relevant. For music artists, however, it is a relevant consideration. If an artist only ever releases one single, their stage name fails to function as a trademark; consumers who like the song—akin to those who may like a one-of-a-kind shirt—cannot build expectations regarding the quality and source of the song.

Once an artist has released a second song under that stage name, however, it no longer serves only to identify the performer. Now, the stage name begins to serve a trademark purpose. For fans of the first song, they can carry expectations of what the second song will sound like even before they listen to it. Just by seeing the artist’s name associated with a new song, a consumer can now make decisions about whether they want to consume it or not. Trademark law has a precise interest in protecting these marketplace consumer expectations.

In this way, an artist’s specimen must show that their name is used in connection with more than one song. A Spotify screenshot bearing the artist’s name in connection with a full album of streamable sound recordings would generally satisfy this requirement. Artists such as Demi Lovato, Selena Gomez, and the Jonas Brothers received an Office Action on this grounds.

But the USPTO’s requirements get even more technical than that. A screenshot of a CD available for purchase that does not show individual songs available for streaming or purchase, for example, does not serve as a series – even though the CD contains numerous sound recordings.

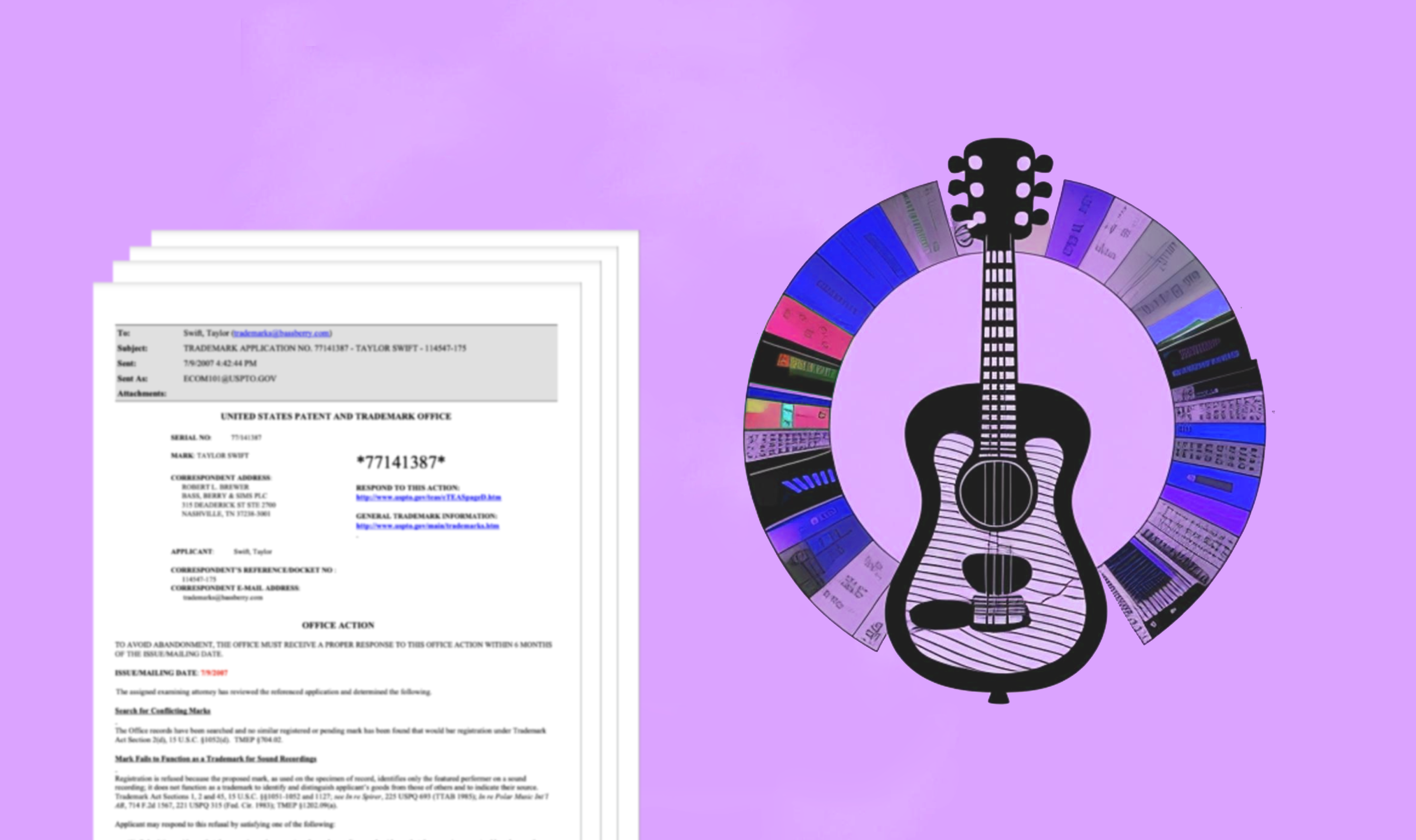

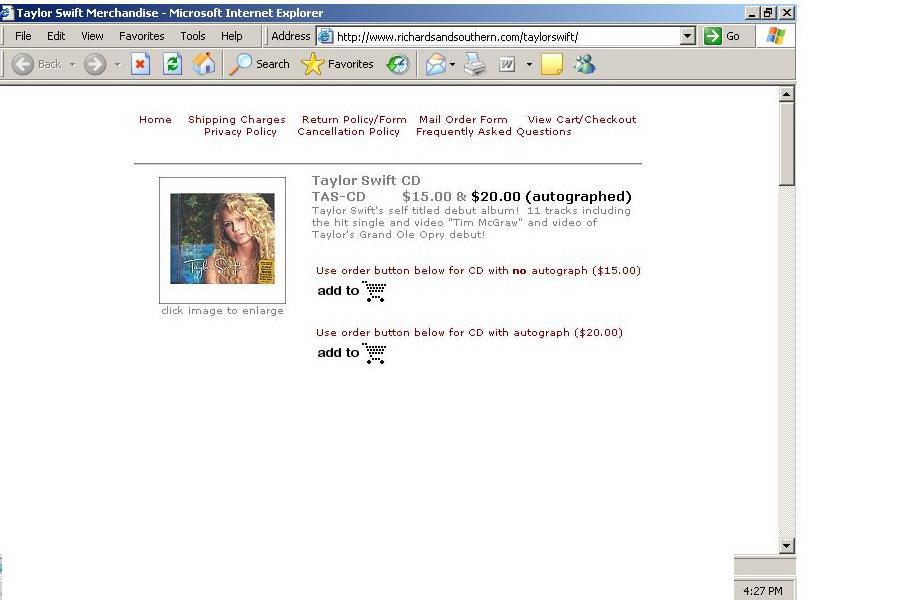

Consider Taylor Swift’s 2007 application to register TAYLOR SWIFT in connection with Series of musical sound recordings; pre-recorded [audio cassettes, ] compact discs, DVD's [ and video tapes ] featuring performances by an individual [; mouse pads ]. Swift submitted the following specimen with her application:

Specimen as it appears in Swift’s application, US Serial No. 77141387.

The Examining Attorney assigned to her application issued an Office Action dated July 9, 2007. One of the noted reasons for the Office Action was Swift’s failure to demonstrate use of her TAYLOR SWIFT mark in relation to a series of sound recordings since the submitted specimen only depicted a single CD. Specifically, the Examining Attorney provided that:

Registration is refused because the proposed mark, as used on the specimen of record, identifies only the featured performer on a sound recording; it does not function as a trademark to identify and distinguish applicant’s goods from those of others and to indicate their source.

…

The fact that applicant identifies the goods as a series of musical sound recordings is not, in itself, sufficient to overcome this refusal.

Swift had two options through which she could successfully respond. Both options required submitting a new specimen that demonstrates use on a series of sound recordings prior to the filing date of the application. “Evidence of a series includes copies or photographs of at least two different CD covers or similar packaging for prerecorded works.”

Additionally, Swift had to submit either (1) evidence that her name is recognized by others as the source of a series of recordings, or (2) evidence that she controls the quality of the recordings and controls use of her name, such that her name has come to represent an assurance of quality to the public. The Examining Attorney provided examples for each:

Evidence that the name is recognized by others as a source of the series includes advertising that promotes the name as the source of the series, third-party reviews showing use of the name by others to refer to the series, and/or declarations from the sound recording industry, retailers, and purchasers showing recognition of the name as an indicator of the source of a series of recordings.

Evidence of control over the quality of the recordings and use of the name includes licensing contracts or similar documentation.

Swift submitted several new specimen samples to satisfy the above requirements, including a screenshot of her Sounds of The Season: The Taylor Swift Holiday Collection EP, a screenshot for her eponymous deluxe edition album, and screenshots and photocopies of publications such as That’s Country, Billboard, and AOL Music which showcased the notoriety and success of her music (demonstrating that others recognized TAYLOR SWIFT as the source of the songs). These submissions were enough to overcome the Examiner’s refusal to register on specimen grounds.

If an artist or band wants to register their name as a trademark for downloadable sound recordings, they must submit a specimen that shows their name in a manner that is available for download. A screenshot of a Spotify or Apple Music catalog would not suffice for downloadable goods. Instead, the Examining Attorney will be looking for some ‘call to action’ that demonstrates downloadability. A webpage featuring a download button next to available songs is the best example for this.

In the absence of this clear evidence, the specimen must show some evidence that the sound recordings are available for download. Screenshots from the iTunes Store can be good material to submit if primarily offered to supplement proof that the songs are available to download, since the iTunes Store unfortunately lacks the term “Download” on its album pages. A screenshot of an artist’s music available on BandCamp can serve as good evidence, since the webpage unequivocally provides that the files are available for “Streaming + Download” as either a “Free Download” or “high-quality download in MP3”, depending on the artist’s preferences.

Swift’s application did not face a refusal on these grounds, so I apologize for not having a Taylor Swift example to demonstrate this refusal. Nonetheless, proof of downloadability for downloadable goods is a concern that musicians should consider as they proceed to the trademark registration application process.

Artists who use their legal name as their performer name may run into this obstacle to registration. The USPTO will only issue a registration certificate for marks that bear an individual’s name if the application includes a signed statement by the named individual consenting to the use of their name in the applied-for trademark. Even if the applicant is the individual mentioned, that alone is not enough: the individual’s signed consent is required. A few who have received an Office Action for this reason: Kendrick Lamar, Lady Gaga, Harry Styles, Kanye West, Travis Scott, Mac, Miller, Post Malone, Selena Gomez, and Rihanna.

Consider again Taylor Swift’s 2007 trademark application. The July 9th Office Action also required Swift to indicate if the applied-for mark TAYLOR SWIFT identified a living individual, and, if it did, required that she submit evidence of consent to register the name.

In response to this, Swift submitted the following signed statement:

I, Taylor Swift, hereby give consent to the registration of the trademark, TAYLOR SWIFT, for a “series of musical sound recordings; pre-recorded audio cassettes, compact discs, DVD’s and video tapes featuring performances by an individual; and mouse pads” in International Class 9, “clothing, namely, shirts, T-shirts, sweatshirts, jerseys, hats and caps” in International Class 25, “entertainment services in the nature of the rendition of live musical performances by an individual” in International Class 41, and authorize the registration of the name as a trademark for such goods and services with the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

This declaration satisfied the Examiner’s consent-of-a-living-individual concerns, and Swift received her trademark registration certificate on June 03, 2008.

Because of how common these kinds of refusals are for musical act trademarks, any such performer looking to register their name with the USPTO should be aware of these issues and be prepared to address them within their applications. If you have already filed, you may expect an Office Action on one of these grounds. No matter—just be prepared to respond accordingly. From the time an Office Action is issued, you only have three months to file your response, so make sure that you do so swiftly.

To view a version of this article with full citations in footnote form, click the PDF link here.